Collection: Frank Miller

Frank Miller didn't just write great comics — he changed what comics were allowed to be. Born in 1957 and raised in Montpelier, Vermont, Miller moved to New York City as a teenager with a portfolio under his arm and an obsession with crime fiction, noir cinema, and Japanese manga that would eventually fuse into one of the most distinctive visual and narrative voices the medium has ever produced. He broke in through small fill-in work at DC and Marvel in the late 1970s before landing on Daredevil — and then everything changed.

His run on Daredevil (1979–1983), first as artist and then as writer-artist, transformed a struggling second-tier Marvel title into one of the most critically acclaimed comics of its era. Drawing heavily on film noir, samurai cinema, and the gritty street-level energy of 1970s New York, Miller introduced Elektra, reinvented the Hand, and made Hell's Kitchen feel genuinely dangerous. Daredevil: Born Again (1986), his return to the character with artist David Mazzucchelli, remains one of the greatest single story arcs in Marvel history — a brutal, redemptive dismantling and rebuilding of Matt Murdock that has never been surpassed.

But it was 1986 that cemented Miller as one of the most important figures in the history of American comics. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns — a four-issue prestige format series set in a dystopian future where a 55-year-old Bruce Wayne comes out of retirement — arrived the same year as Watchmen and together they fundamentally redefined what superhero comics could be. Dark, operatic, politically charged, and visually revolutionary, The Dark Knight Returns dragged Batman into a new era and influenced every serious interpretation of the character that followed, from Tim Burton's films to Christopher Nolan's trilogy. Batman: Year One (1987), with Mazzucchelli again, followed as the definitive retelling of Batman's origin — lean, grounded, and novelistic in its precision.

Miller's creator-owned work is equally essential. Ronin (1983) was a pioneering experiment in manga-influenced American comics. Sin City, launched in 1991, is a starkly black-and-white neo-noir universe built from pure visual invention and hard-boiled pulp storytelling — arguably the most complete expression of Miller's aesthetic sensibilities as both writer and artist. 300 (1998), painted by Lynn Varley, retold the Battle of Thermopylae as a thunderous graphic epic that reads like mythology carved in stone.

In Hollywood, Miller's impact has been enormous and direct. He co-directed Sin City (2005) with Robert Rodriguez — a visually groundbreaking film that translated his stark black-and-white artwork almost panel-for-panel to the screen and was nominated for the Palme d'Or at Cannes. He executive produced Zack Snyder's 300 (2007), which grossed over $456 million worldwide and sparked an entire era of stylized, high-contrast action filmmaking. Sin City: A Dame to Kill For followed in 2014. Earlier in his Hollywood career he wrote the screenplays for RoboCop 2 and RoboCop 3 in the early 1990s. His Batman: Year One was adapted as a DC animated film in 2011, and The Dark Knight Returns received a celebrated two-part animated adaptation in 2012–2013. His YA novel Cursed, co-written with Thomas Wheeler, was adapted as a Netflix series in 2020. In 2024, the documentary Frank Miller: American Genius was released, chronicling his half-century career following a near-death experience.

Miller was inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 2015, having already won every major comics industry award available to him. Few creators in any medium can point to a body of work that so fundamentally shaped the culture around them — and fewer still did it while also being the best artist in the room.

-

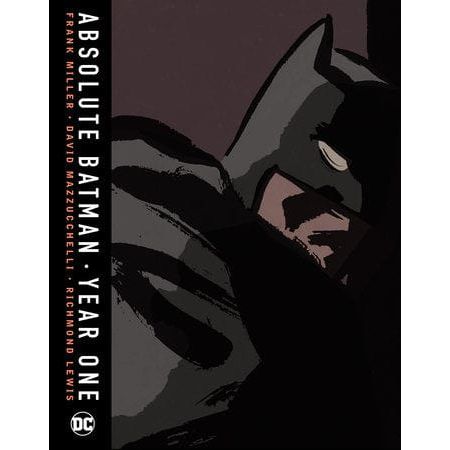

ABSOLUTE BATMAN YEAR ONE HC

Regular price Afl170.00 AWGRegular priceAfl250.00 AWGSale price Afl170.00 AWG-32% -

-36%

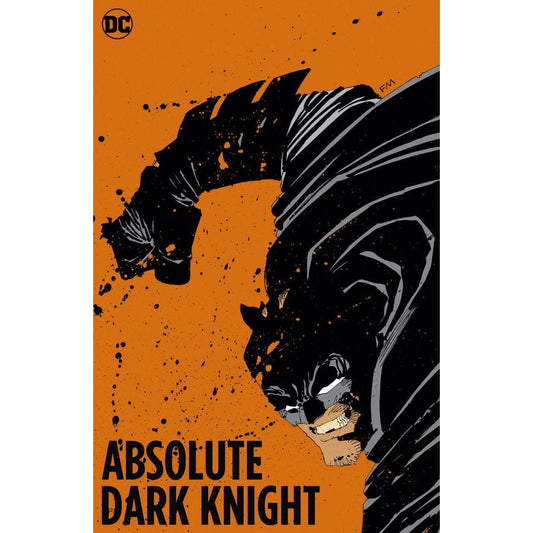

-36%ABSOLUTE DARK KNIGHT

Regular price Afl145.00 AWGRegular priceAfl230.00 AWGSale price Afl145.00 AWG-36% -

Frank Miller's Sin City Volume 1: The Hard Goodbye (Deluxe Edition)

Regular price Afl140.00 AWGRegular priceAfl200.00 AWGSale price Afl140.00 AWG-30% -

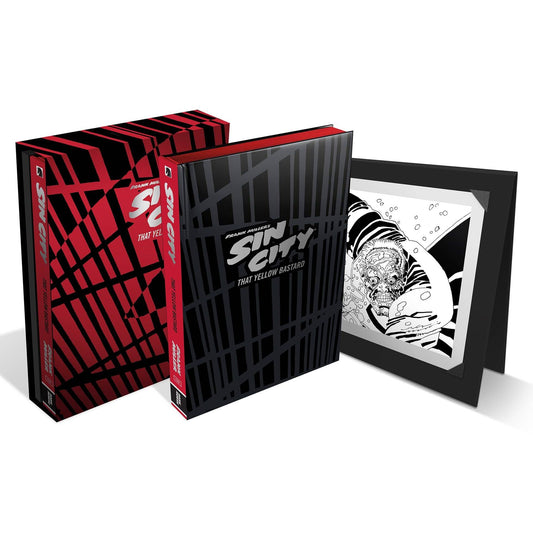

SIN CITY DLX HC VOL 04 THAT YELLOW BASTARD (4TH ED)

Regular price Afl140.00 AWGRegular priceAfl200.00 AWGSale price Afl140.00 AWG-30% -

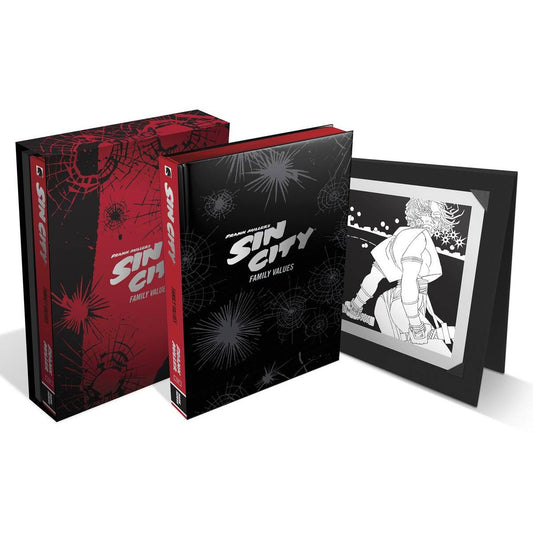

Frank Miller's Sin City Volume 5: Family Values

Regular price Afl140.00 AWGRegular priceAfl200.00 AWGSale price Afl140.00 AWG-30% -

Frank Miller's Sin City Volume 2: A Dame to Kill For (Deluxe Edition)

Regular price Afl140.00 AWGRegular priceAfl200.00 AWGSale price Afl140.00 AWG-30% -

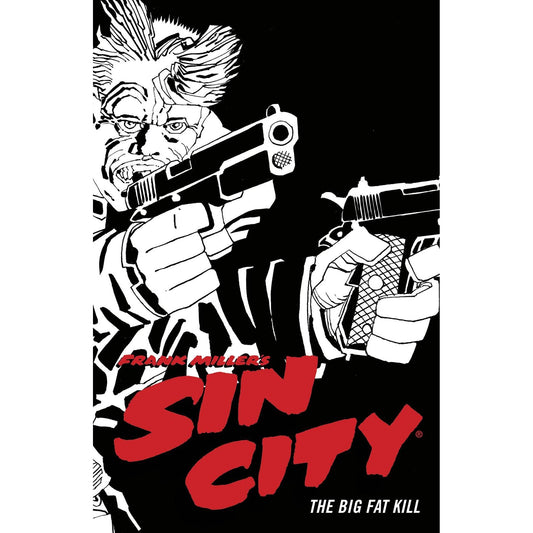

SIN CITY DLX HC VOL 03 THE BIG FAT KILL (4TH ED) (MR)

Regular price Afl140.00 AWGRegular priceAfl200.00 AWGSale price Afl140.00 AWG-30% -

Frank Miller's Sin City Volume 7: Hell and Back

Regular price Afl140.00 AWGRegular priceAfl200.00 AWGSale price Afl140.00 AWG-30% -

David Mazzucchelli's Batman Year One Artist's Edition

Regular price Afl230.00 AWGRegular priceAfl276.00 AWGSale price Afl230.00 AWG-16% -

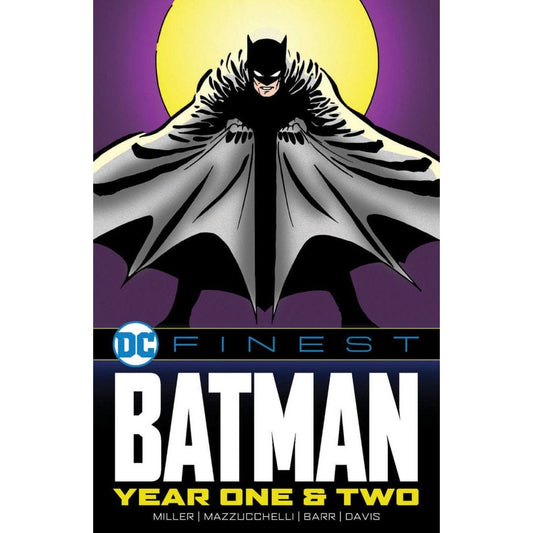

DC FINEST: BATMAN: BATMAN: YEAR ONE & TWO TPB

Regular price Afl65.00 AWGRegular priceAfl74.00 AWGSale price Afl65.00 AWG-12% -

DAREDEVIL: BORN AGAIN [MARVEL PREMIER COLLECTION]

Regular price Afl19.00 AWGRegular priceAfl28.00 AWGSale price Afl19.00 AWGSold out -

David Mazzucchelli’s Daredevil Born Again Artist’s Edition

Regular price Afl221.00 AWGRegular priceAfl276.00 AWGSale price Afl221.00 AWG-19% -

DC COMPACT COMICS BOX SET On Sale: 11/3/26

Regular price Afl70.00 AWGRegular priceAfl92.00 AWGSale price Afl70.00 AWGSold out

![DAREDEVIL: BORN AGAIN [MARVEL PREMIER COLLECTION]](http://www.panelboundcomics.com/cdn/shop/files/9781302965983.jpg?v=1754425219&width=533)